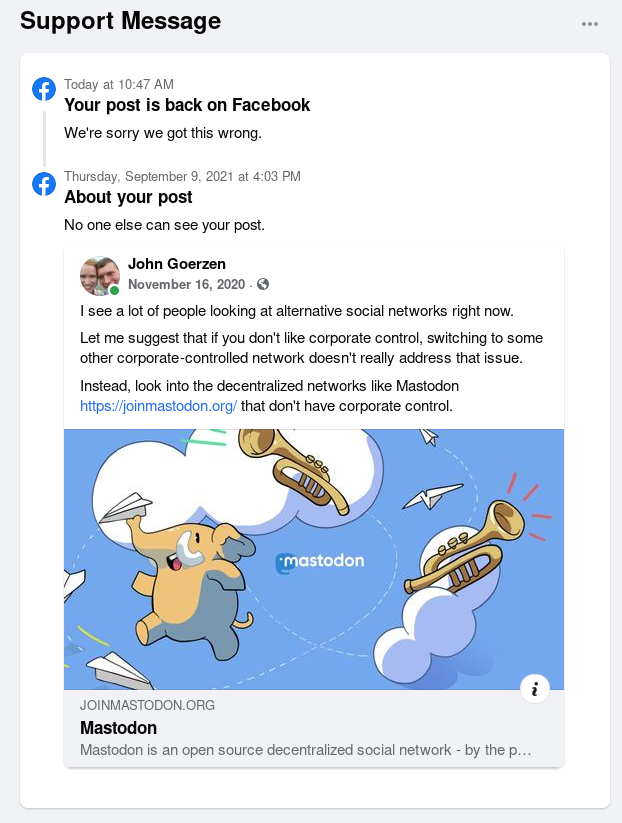

In light of this week’s announcement by Meta (Facebook, Instagram, Threads, etc), I have been pondering this question: Why am I, a person that has long been a staunch advocate of free speech and encryption, leery of sites that talk about being free speech-oriented? And, more to the point, why an I — a person that has been censored by Facebook for mentioning the Open Source social network Mastodon — not cheering a “lighter touch”?

The answers are complicated, and take me back to the early days of social networking. Yes, I mean the 1980s and 1990s.

Before digital communications, there were barriers to reaching a lot of people. Especially money. This led to a sort of self-censorship: it may be legal to write certain things, but would a newspaper publish a letter to the editor containing expletives? Probably not.

As digital communications started to happen, suddenly people could have their own communities. Not just free from the same kinds of monetary pressures, but free from outside oversight (parents, teachers, peers, community, etc.) When you have a community that the majority of people lack the equipment to access — and wouldn’t understand how to access even if they had the equipment — you have a place where self-expression can be unleashed.

And, as J. C. Herz covers in what is now an unintentional history (her book Surfing on the Internet was published in 1995), self-expression WAS unleashed. She enjoyed the wit and expression of everything from odd corners of Usenet to the text-based open world of MOOs and MUDs. She even talks about groups dedicated to insults (flaming) in positive terms.

But as I’ve seen time and again, if there are absolutely no rules, then whenever a group gets big enough — more than a few dozen people, say — there are troublemakers that ruin it for everyone. Maybe it’s trolling, maybe it’s vicious attacks, you name it — it will arrive and it will be poisonous.

I remember the debates within the Debian community about this. Debian is one of the pillars of the Internet today, a nonprofit project with free speech in its DNA. And yet there were inevitably the poisonous people. Debian took too long to learn that allowing those people to run rampant was causing more harm than good, because having a well-worn Delete key and a tolerance for insults became a requirement for being a Debian developer, and that drove away people that had no desire to deal with such things. (I should note that Debian strikes a much better balance today.)

But in reality, there were never absolutely no rules. If you joined a BBS, you used it at the whim of the owner (the “sysop” or system operator). The sysop may be a 16-yr-old running it from their bedroom, or a retired programmer, but in any case they were letting you use their resources for free and they could kick you off for any or no reason at all. So if you caused trouble, or perhaps insulted their cat, you’re banned. But, in all but the smallest towns, there were other options you could try.

On the other hand, sysops enjoyed having people call their BBSs and didn’t want to drive everyone off, so there was a natural balance at play. As networks like Fidonet developed, a sort of uneasy approach kicked in: don’t be excessively annoying, and don’t be easily annoyed. Like it or not, it seemed to generally work. A BBS that repeatedly failed to deal with troublemakers could risk removal from Fidonet.

On the more institutional Usenet, you generally got access through your university (or, in a few cases, employer). Most universities didn’t really even know they were running a Usenet server, and you were generally left alone. Until you did something that annoyed somebody enough that they tracked down the phone number for your dean, in which case real-world consequences would kick in. A site may face the Usenet Death Penalty — delinking from the network — if they repeatedly failed to prevent malicious content from flowing through their site.

Some BBSs let people from minority communities such as LGBTQ+ thrive in a place of peace from tormentors. A lot of them let people be themselves in a way they couldn’t be “in real life”. And yes, some harbored trolls and flamers.

The point I am trying to make here is that each BBS, or Usenet site, set their own policies about what their own users could do. These had to be harmonized to a certain extent with the global community, but in a certain sense, with BBSs especially, you could just use a different one if you didn’t like what the vibe was at a certain place.

That this free speech ethos survived was never inevitable. There were many attempts to regulate the Internet, and it was thanks to the advocacy of groups like the EFF that we have things like strong encryption and a degree of freedom online.

With the rise of the very large platforms — and here I mean CompuServe and AOL at first, and then Facebook, Twitter, and the like later — the low-friction option of just choosing a different place started to decline. You could participate on a Fidonet forum from any of thousands of BBSs, but you could only participate in an AOL forum from AOL. The same goes for Facebook, Twitter, and so forth. Not only that, but as social media became conceived of as very large sites, it became impossible for a person with enough skill, funds, and time to just start a site themselves. Instead of neading a few thousand dollars of equipment, you’d need tens or hundreds of millions of dollars of equipment and employees.

All that means you can’t really run Facebook as a nonprofit. It is a business. It should be absolutely clear to everyone that Facebook’s mission is not the one they say it is — “[to] give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together.” If that was their goal, they wouldn’t be creating AI users and AI spam and all the rest. Zuck isn’t showing courage; he’s sucking up to Trump and those that will pay the price are those that always do: women and minorities.

Really, the point of any large social network isn’t to build community. It’s to make the owners their next billion. They do that by convincing people to look at ads on their site. Zuck is as much a windsock as anyone else; he will adjust policies in whichever direction he thinks the wind is blowing so as to let him keep putting ads in front of eyeballs, and stomp all over principles — even free speech — doing it. Don’t expect anything different from any large commercial social network either. Bluesky is going to follow the same trajectory as all the others.

The problem with a one-size-fits-all content policy is that the world isn’t that kind of place. For instance, I am a pacifist. There is a place for a group where pacifists can hang out with each other, free from the noise of the debate about pacifism. And there is a place for the debate. Forcing everyone that signs up for the conversation to sign up for the debate is harmful. Preventing the debate is often also harmful. One company can’t square this circle.

Beyond that, the fact that we care so much about one company is a problem on two levels. First, it indicates how succeptible people are to misinformation and such. I don’t have much to offer on that point. Secondly, it indicates that we are too centralized.

We have a solution there: Mastodon. Mastodon is a modern, open source, decentralized social network. You can join any instance, easily migrate your account from one server to another, and so forth. You pick an instance that suits you. There are thousands of others you can choose from. Some aggressively defederate with instances known to harbor poisonous people; some don’t.

And, to harken back to the BBS era, if you have some time, some skill, and a few bucks, you can run your own Mastodon instance.

Personally, I still visit Facebook on occasion because some people I care about are mainly there. But it is such a terrible experience that I rarely do. Meta is becoming irrelevant to me. They are on a path to becoming irrelevant to many more as well. Maybe this is the moment to go “shrug, this sucks” and try something better.

(And when you do, feel free to say hi to me at @jgoerzen@floss.social on Mastodon.)